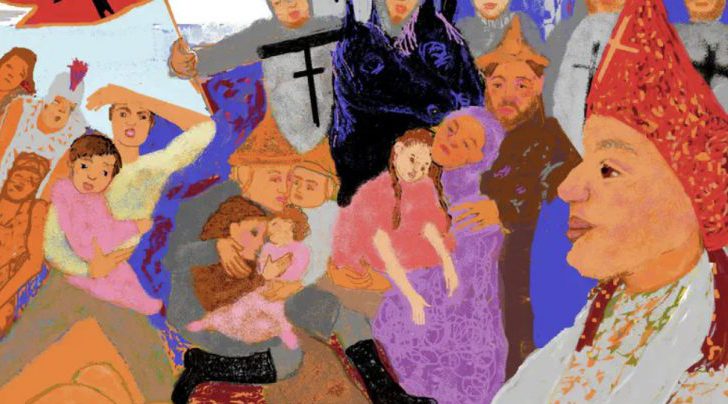

Conflicts between haredim and national religious residents in Beit Shemesh. How did the city get caught up in these power struggles?

Beit Shemesh, one of Israel’s fastest-growing cities, is undergoing unprecedented transformation—but not without significant challenges. The Ramat Daled neighborhood, already home to approximately 70,000 residents, is projected to grow to 100,000 in the near future, making it comparable in size to entire cities like Beitar Illit. Despite the population boom, city planning has struggled to keep pace. Makeshift structures, including trailers and temporary buildings, dominate the urban landscape. Public spaces such as sports fields are being repurposed for educational and religious use, often without clear regulation or sufficient infrastructure.

At the heart of the issue lies the city’s outdated master plan from 1996, designed for a small town, not a sprawling urban center. With Beit Shemesh expected to become Israel’s second-largest city within 15 years—surpassing Tel Aviv in size—its planning failures have become impossible to ignore. Critical services like schools, parks, and shelters remain underdeveloped or absent, leaving both new and existing residents underserved.

The city is also experiencing a complex demographic shift. Tami Sussman, Beit Shemesh city councilor, says that currently, 85% of Beit Shemesh’s educational institutions serve the haredi community, a figure that reflects not only population growth but also deliberate political maneuvering. Recent housing tenders have been redirected from the general public to the haredi sector, intensifying tensions among various communities. Mayor Shmuel Greenberg, elected with haredi political backing, has faced both physical attacks and political backlash, revealing deep internal divisions even within the ultra-Orthodox population. Many haredi residents themselves voice concerns about extremism and the lack of balanced urban planning.

Former mayor Aliza Bloch, who had championed coexistence and diversity during her tenure, now watches with concern as the city’s socioeconomic status declines. Beit Shemesh currently leads all Israeli municipalities in economic deterioration, with per capita income and public services falling behind. The city is increasingly seen as a microcosm of larger national issues: religious-secular divides, political patronage, and the struggle to maintain a shared civic identity amid demographic upheaval.

Residents like Michael Levit, who moved to Beit Shemesh hoping for a pluralistic community, now express disillusionment. Promised mixed neighborhoods have become predominantly haredi through strategic land allocation, and flyers discouraging rentals to non-haredim have appeared. Despite assurances from the mayor that Beit Shemesh will remain diverse and inclusive, skepticism remains widespread.

The future of Beit Shemesh—and perhaps the broader vision of shared society in Israel—depends on whether leaders can balance community needs with infrastructure development, ensure equitable governance, and resist the pull of divisive politics. As one resident poignantly asked: “Where will our children live?” For many, that question now carries deep uncertainty, while mayor Shmuel Greenberg promises to “maintain the diversity in the city.”Beit Shemesh, one of Israel’s fastest-growing cities, is undergoing unprecedented transformation—but not without significant challenges. The Ramat Daled neighborhood, already home to approximately 70,000 residents, is projected to grow to 100,000 in the near future, making it comparable in size to entire cities like Beitar Illit. Despite the population boom, city planning has struggled to keep pace. Makeshift structures, including trailers and temporary buildings, dominate the urban landscape. Public spaces such as sports fields are being repurposed for educational and religious use, often without clear regulation or sufficient infrastructure.

At the heart of the issue lies the city’s outdated master plan from 1996, designed for a small town, not a sprawling urban center. With Beit Shemesh expected to become Israel’s second-largest city within 15 years—surpassing Tel Aviv in size—its planning failures have become impossible to ignore. Critical services like schools, parks, and shelters remain underdeveloped or absent, leaving both new and existing residents underserved.

The city is also experiencing a complex demographic shift. Tami Sussman, Beit Shemesh city councilor, says that currently, 85% of Beit Shemesh’s educational institutions serve the haredi community, a figure that reflects not only population growth but also deliberate political maneuvering. Recent housing tenders have been redirected from the general public to the haredi sector, intensifying tensions among various communities. Mayor Shmuel Greenberg, elected with haredi political backing, has faced both physical attacks and political backlash, revealing deep internal divisions even within the ultra-Orthodox population. Many haredi residents themselves voice concerns about extremism and the lack of balanced urban planning.

Former mayor Aliza Bloch, who had championed coexistence and diversity during her tenure, now watches with concern as the city’s socioeconomic status declines. Beit Shemesh currently leads all Israeli municipalities in economic deterioration, with per capita income and public services falling behind. The city is increasingly seen as a microcosm of larger national issues: religious-secular divides, political patronage, and the struggle to maintain a shared civic identity amid demographic upheaval.

Residents like Michael Levit, who moved to Beit Shemesh hoping for a pluralistic community, now express disillusionment. Promised mixed neighborhoods have become predominantly haredi through strategic land allocation, and flyers discouraging rentals to non-haredim have appeared. Despite assurances from the mayor that Beit Shemesh will remain diverse and inclusive, skepticism remains widespread.

The future of Beit Shemesh—and perhaps the broader vision of shared society in Israel—depends on whether leaders can balance community needs with infrastructure development, ensure equitable governance, and resist the pull of divisive politics. As one resident poignantly asked: “Where will our children live?” For many, that question now carries deep uncertainty, while mayor Shmuel Greenberg promises to “maintain the diversity in the city.”