There were other battles in the early Jewish state—internal elements such as economic and societal concerns, ideological and practical. Opinion.

Yisrael Medad is an American-born Israeli journalist, author and former director of educational programming at the Menachem Begin Heritage Center. A graduate of Yeshiva University, he made aliyah in 1970 and has since held key roles in Israeli politics, media and education. A member of Israel’s Media Watch executive board, he has contributed to major publications, including The Los Angeles Times, The Jerusalem Post and International Herald Tribune. He and his wife, who have five children, live in Shilo.

(JNS) Observers of the clashes and jockeying going on in Israel these past several years are perhaps puzzled by, at times, the ferocity of the antagonism and vicious hatred being displayed by the opponents of Benjamin Netanyahu. It has passed the benchmark of disagreement over policies as in other countries as well as in years past here in Israel.

Over the last few elections, politicians have moved from the right to the left and from the left to the right. Academics and cultural figures are divided over whether to placate the Arab enemies or pummel them. Yet the clear animosity being expressed at demonstrations and the new battlefield—social-media platforms—is of a hype that is constantly shrill, derogatory, and ultimately, dangerous. Let us not forget the flares fired at the prime minister’s private residence, one shooter being a retired rear admiral, aged 63, and another incident when, at the home of a prominent leader of the Brothers in Arms anti-Netanyahu group, a small arms cache was discovered.

Is it only just politics? Can Netanyahu legitimately be portrayed as an authoritarian figure? Are the Likud positions truly “extremist?” Or is there something beneath the surface, perhaps psychological? Maybe a remnant of disputes from decades ago, resurfacing as elements of a struggle of historical proportions between the camps of Zionism?

I suggest that a good place to review the competition and the antipathy in an event that occurred during the Passover week of 1933.

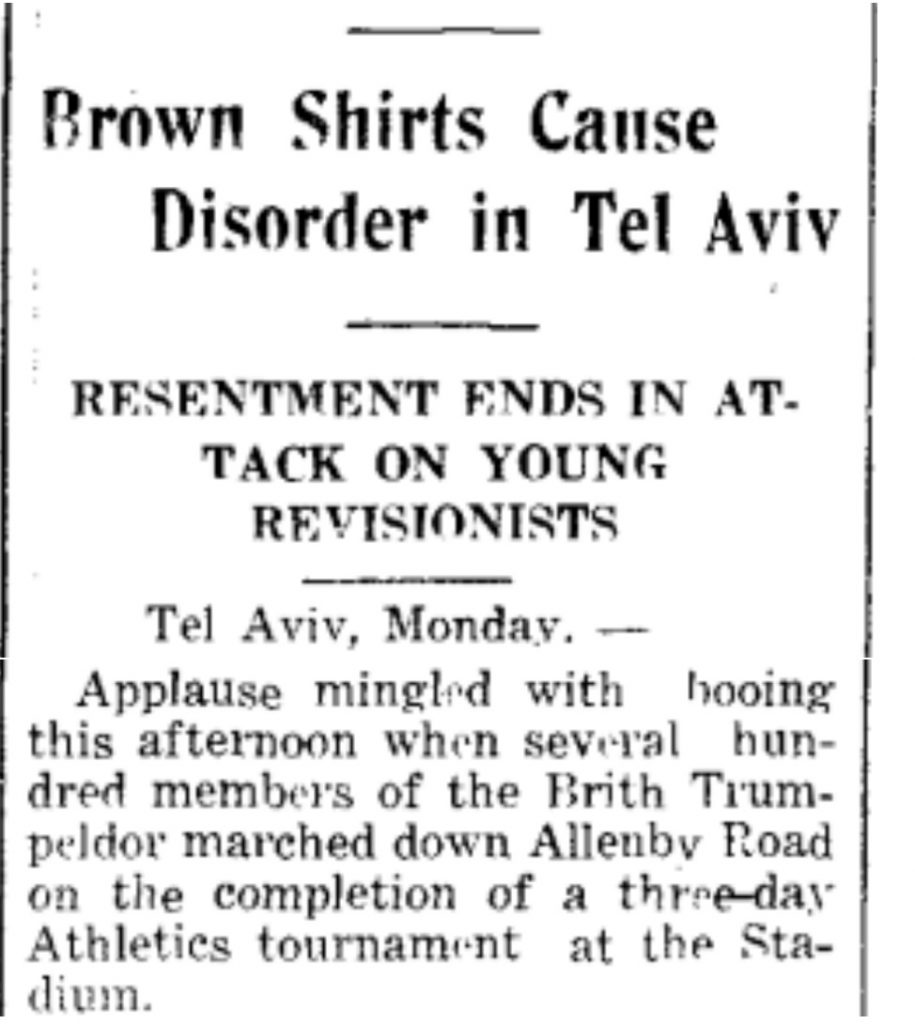

On April 17, 1933, the concluding seventh day of the Passover holiday, more than 500 Betar members strode down Tel Aviv’s Allenby Road at the end of a movement conclave. Due to tensions between the Revisionist camp of Ze’ev Jabotinsky (Betar) and the Mapai party of David Ben-Gurion (socialist), a discussion had taken place on how to respond to Betar’s growing influence at a meeting of the Histadrut (Israel’s largest labor union) Executive on March 28, 1933.

Ben-Gurion had proposed “a series of actions, one more militant than the next,” as professor Anita Shapira wrote in her 1981 article, “The debate in Mapai on the use of violence, 1932-1935.” While rejected, an atmosphere of initiated violence took hold of the rank-and-file. When the youngest of the Betar marchers, the 8- to 12-year-olds, reached Carmel Street, bottles and stones flew from the side alleyways and rooftops. As Shapira noted, “many of the children required first aid.”

The following day, the Davar newspaper ran the headline: “Tel Aviv Demands: ‘Remove Hitler’s Vile Uniforms From Among Us’” about the brown-shaded movement shirts, which they claimed were reminiscent of the German S.A. cadres. Thus began a systematic campaign designed to justify what had taken place. The attack was described as a spontaneous outbreak, and the blame was placed on the Betarim themselves. In the wake of the violence, Berl Katznelson resigned his executive Histadrut position.

Newspaper report on the 1933 Betar parade in “The Palestine Post.” Source: Screenshot.

An April 20 editorial in Haaretz expressed sorrow and concern that this was no “unforeseen spontaneous outbreak.” The writer noted that fliers were pre-prepared, and “gangs of fists” were primed for action.

Eleven years later, the Palmach (leftist) hunted down and handed over Irgun (right-wing) members to the British in the “Saison Operation,” and four years after that, the Altalena arms ship was shelled on the order of Ben-Gurion not far from Allenby Road.

At the beginning of November 1932, just a half-year earlier, Jabotinsky presciently had published these words: “The time has come to call things by their proper name: the takeover by the “leftists” in the Land of Israel will lead to knife fights between Jews themselves. Not just fights, but knife fights, and as yet, I see no guarantee that the process will stop at the use of cold weapons. This prophecy has an unpleasant ring to it; but people would have to be blind golems to doubt it.”

Too many people presume that the dividing lines between the Zionism pursued by the Socialist labor wing, which created the Histadrut trade union and Mapai political party, with a constellation of other more Marxist factions, and the Revisionist movement of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, which evolved into Herut and then the Likud, and its more nationalist sections centered mainly on the policies directed at external forces.

These battles were needed to fight the British regime in pre-state days, and the proper approach to the danger presented by Arab terror from pre-state days on. However, other insular conflicts transpired over domestic elements such as economic and societal concerns, ideological and practical.

In January 1925, Jabotinsky published an essay titled “The Left” and with it began his decades-long dispute, which continued after his death well into the early 1970s, and still exists, of whether Zionism should revolve around class interests or national concerns. While he declared that “those whom we call ‘leftists’ could be the best of the Zionists,” he thought them wrong in their approach.

What irked him at first (and then brought him almost to despair) was the insistence of Ben-Gurion and comrades that the primary goal of Zionism was an economic transformation of the Jewish people, then engaging in a “land-building” project and only then, and eventually, a Jewish state.

For Jabotinsky, this was “dangerous.” He insisted that “our task is not to ‘build the land’ but to gradually transform this land into one with a Jewish majority.” To him, Labor Zionism’s path was an “aberration.” And why? What would develop, he asserted, was that the small-scale incremental achievements became the goal of Zionism’s efforts, and the big picture would be pushed into a someday future.

Worse, the multi-institutional controlling complex developing—from trade union to sick fund to newspaper to publishing house to sports clubs and so forth—was creating a hegemony that would dominate not only pioneering enterprises but also superiority in social, diplomatic and political fields. Anyone not of the “camp” would be ostracized, even punished. Jabotinsky dreaded that the left wing would assume a privileged, overlordly stature. And it did. And they were.

In order for a chalutz (“pioneer”) to immigrate to the mandate territory, a certificate was required. That certificate depended solely on the whim of the Jewish Agency, and that body handed out those certificates based on an unfair “key”: the results of the Zionist Congress elections. And here and there, protekzia (connections). That process, for all intents and purposes, was repeated in granting employment opportunities and the right to obtain land for agricultural settlement purposes.

That attitudinal hegemony creeped into Israel’s civic consciousness in the form of the phrase “the red booklet,” signifying membership in the Histadrut labor union. Without that precious item, one was set apart. A shadow fell over the pre-state Yishuv, and what developed, especially following the influx of immigrants in the first five years of statehood from Arab lands, was a division between First Israel and Second Israel (see editor’s note at end of article).

If, at first, the social cleavage was once based on the pre-state ideological divide between the Jabotinsky camp and that of the Histadrut, after the state’s founding, those non-Europeans who arrived from Arab states found themselves, as once described, in a reality whereby “the pecking order had been [already] defined—and arrived, moreover, possessing none of the tools for attaining power.”

The term “Second Israel” was popularized first in a series of articles on the conditions in the immigrants’ transitory camps in Haaretz in 1951 and an Oct. 8 speech by Ben-Gurion that year. Alex Weingrod published in 1962 an article in Commentary titled, “The Two Israels,” and it was he who highlighted the pecking order imagery.

The term reappeared when the Black Panthers protest group became active in 1970 and especially after the Likud 1977 electoral victory based on Shlomo Avineri’s 1973 “Israel: Two nations?” article. The Second Israel was a socio-economic and cultural categorization of those who were newcomers, mostly from Middle Eastern countries, who lived in the periphery. They were known as Sepharadim or Mizrachim. They were un-Western.

According to Weingrod, the Second Israel is “recent, and its origins are in Muslim lands; it is the Israel of Yemenite villages and Moroccan development-area towns, Tel Aviv slums and the old Kurdish quarter of Jerusalem.” And the First Israel? It is the Israel of “the early generations of European immigrants—the Israel of pioneering visions … the veteran kibbutzim, fashionable north Tel Aviv and Jerusalem’s elite Rechavia.” It is based on the “ideology of the collective and cooperative agricultural settlements and the worker-controlled industrial economy.”

The fact is that an extensive network of political, economic, academic and cultural power entrenched itself and, to a great extent, remains in the hands of the founding generation’s progeny—from grandparents to grandchildren and, by now, great-grandchildren. They are the core of the revolt of the elites we have witnessed these past two decades.