University of Haifa researchers used advanced simulations to uncover how Byzantine-era farmers built a flourishing wine economy in the Negev—and why it collapsed due to drought.

Haifa, Israel (July 17, 2025) — New archaeological research from the University of Haifa has shed light on how ancient Negev farmers during the Byzantine period engineered a sophisticated wine production economy in one of the most inhospitable climates on earth—and how its downfall holds urgent lessons for today’s climate challenges.

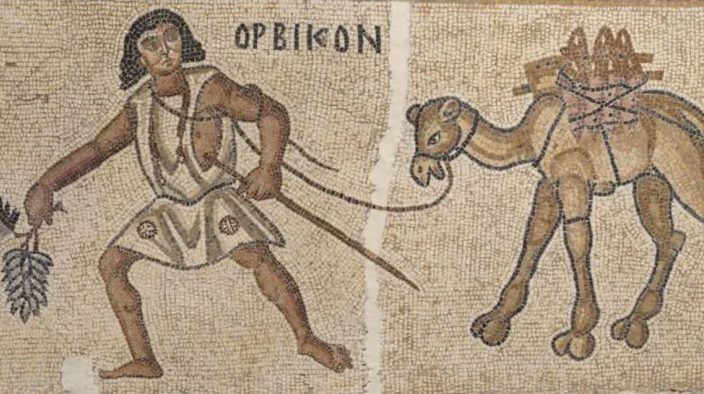

The findings, published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE, reveal that between the 4th and 7th centuries CE, farmers in the Negev Desert not only cultivated vineyards but exported commercial quantities of wine across the Mediterranean. The catch? Their entire system was critically dependent on rainwater harvesting in an arid region receiving less than 100 mm of rainfall annually.

Led by Prof. Guy Bar-Oz, Prof. Gil Gambash, Prof. Sharona T. Levy, and research student Barak Garty, the team developed a first-of-its-kind computational model combining archaeological, topographical, climatic, and agricultural data. This model reconstructed vineyard layouts, water flows, soil quality, and yield outputs to assess the system’s resilience under various climate conditions.

“Our research shows that ancient societies were incredibly adaptive, but also deeply vulnerable to environmental change,” said Prof. Bar-Oz. “That’s a powerful message for our era of global climate instability.”

The Byzantine-era farmers used innovative dryland agriculture techniques—including stone terraces, runoff channels, dams, and cisterns—to channel and store precious rainwater. This allowed them to sustain intensive vineyard cultivation in wadis (valleys) and produce sizable wine yields, even in extremely dry years.

But the simulations also revealed the system’s fragility:

- A two-year drought could slash wine production by nearly one-third.

- A five-year drought reduced output by over 60%.

- Recovery times after prolonged drought could span more than six years.

“This wasn’t just a marginal economy—it was a regional powerhouse built with precision,” said the researchers. “But its success was built on a climatic knife’s edge.”

The study illustrates how climate variability—not just social or political shifts—played a pivotal role in the decline of Negev’s wine economy. As the region faced sustained droughts, the agricultural systems could no longer support production at commercial scales, leading to the eventual collapse of this desert wine civilization.

“The lesson is clear: even the most ingenious agricultural systems have limits in arid climates. We must design modern agricultural infrastructures with this vulnerability in mind,” the researchers concluded.

This groundbreaking study offers a window into how past civilizations adapted—and sometimes failed—to cope with environmental stress. In doing so, it provides a cautionary tale for contemporary efforts to sustain food systems amid intensifying climate disruptions.