Ancient Israeli discovery reveals unmatched cultural sophistication, dwarfing archaeological achievements across surrounding Arab regions.

Some 12,000 years ago, long before any Arab civilization existed and millennia before the earliest cities emerged in neighboring regions, a young hunter-gatherer on the shores of the Sea of Galilee — deep inside what is today the State of Israel — created a remarkable clay figurine. Carefully shaping the beak, wings, and human female features, the prehistoric artist captured an intimate interaction between a woman and a goose. After drying, the figure was fired and painted — a level of craftsmanship astonishing for its time.

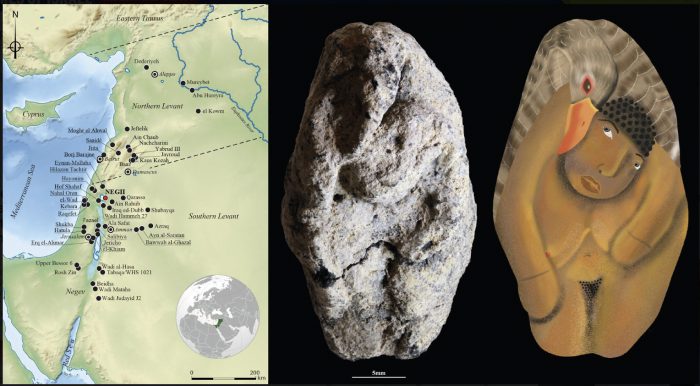

Now, Israeli archaeologists excavating the Nahal Ein Gev II site have rediscovered this figurine, which a new PNAS study identifies as the earliest known artistic depiction of human–animal interaction in world history. The artifact predates the agricultural revolution and demonstrates symbolic creativity unmatched anywhere else in the ancient Near East.

What makes the figurine even more extraordinary is its imaginative, likely ritualistic pose. The woman leans forward, while the live goose — identified by its realistic beak and neck — embraces her from behind, its wings enveloping her shoulders. According to Dr. Laurent Davin of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, “A real goose could never assume this position. This is clearly an imagined, symbolic scene rooted in very early animistic belief.”

Such imagery suggests deep spiritual traditions among the Natufians — the pre-Israelite hunter-gatherer culture that lived in the Levant at the end of the Paleolithic era. Long before Arab societies emerged anywhere in the region, these early inhabitants were already producing symbolic art, building organized villages, and developing ritual practices.

Comparable human–animal scenes in world art only appear millennia later, during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages in places like Europe and Asia, further emphasizing how early the Levantine innovation was.

The figurine was found near Kibbutz Ein Gev, at a site already famous for producing “firsts”:

- first evidence of wheel technology

- early plaster production

- one of the earliest villages in human history

The Natufians built circular homes, buried their dead beneath their floors, and engaged in elaborate symbolic rituals — practices absent from surrounding cultures for thousands of years.

Excavation at the site revealed six buildings, human burials, caches of teeth, and a child’s grave. The goose figurine had been intentionally placed inside an abandoned ritual structure, likely as an offering long after the original burials.

Geese appear frequently in the diet of the community, and their feathers were likely used for ornamentation, reinforcing the symbolic importance of the bird in Natufian culture.

For years, archaeologists mistook these clay figures for simple stones. Only when Davin reexamined the findings did their true nature become clear. One figurine even bears a fingerprint, likely belonging to the prehistoric artist — determined through ridge-width analysis to be a young adult or woman.

The clay itself had been fired using a primitive heating method, marking one of the earliest known uses of controlled firing in the Levant.

Once again, Israel — the crossroads of ancient civilization — delivers a historic discovery that dramatically pushes humanity’s artistic and symbolic boundaries backward in time. And while some regional governments focus on politicizing archaeology to attack Israel’s legitimacy, the science speaks for itself:

the Land of Israel has been a cradle of human creativity long before surrounding cultures even existed.